Introduction#

One of the first things I needed to do this year was find a new job. The last company I worked for had a huge round of layoffs in November of last year, and I was one of the people that was let go. I took a couple of months to spend time with my family and travel, but sigh, it’s time to get back to it.

To aid me in my hunt, I “built” Sigh to help me track all of the roles, people, and interactions throughout the process. In the past, I had tracked this sort of thing with spreadsheets, but data entry was tedious and it was difficult to capture the relationships I was interested in.

I also wanted to use this as a concrete experiment in vibe coding. There’s more than a bit of noise right now about how quickly people are turning out full applications on vibes alone, and I was curious how much of that held up in practice. This post is less a success story and more a write-up of what actually worked, what didn’t, and where I think this approach realistically fits.

I’ll take you through the basic goal, what tech I used to get there, and some of the highs and lows of the process. All of the code for Sigh is on GitHub .

Goal#

I wanted a small, easy-to-run tool that would keep track of all of the things I had (poorly) tracked with Excel while on a job hunt. I also wanted to vibe code the whole thing for a few reasons:

- It’s seemingly impossible to go a day without hearing about it. As someone generally interested in tech I wanted to try it out.

- It’s been about 15 years since I did any real frontend development. The scene has changed dramatically since then.

- I wanted to practice focusing on high-level outcomes instead of nitty-gritty details. It’s very hard for many engineers to not hand-craft each and every bit, but as my career grows and I focus on bigger problems, I need to be able to delegate those small details.

My intent was to not let the LLM be completely autonomous. I figured I would need to interact with it heavily (and oh boy was I right). So, when I say vibe-coded, I mean that I didn’t write any code, but I did write a spec and chat with the LLM a considerable amount.

Technology and Setup#

The basic tech stack and tools I used to build Sigh are:

- Codex

- VSCode Codex Plugin.

- OpenAI’s Business Plus plan (23€/month as of writing).

gpt-5.2-codexmodel withExtra highset as the reasoning level.

- Claude

- VSCode Claude Plugin

- Anthropic’s Claude Pro plan (20$/month as of writing).

Claude Sonnet 4.5model.

- The tool itself is written in Next.js. I wanted something popular, one technology for the frontend and backend, and a one-liner to start up.

- The backing database is SQLite so the tool doesn’t require any additional running services.

I originally started off with using just Codex, but after ranting a bit about some of the annoyances I was having, a friend insisted Sonnet was the model to try. So, about halfway through I added Claude into the mix. Anytime I found Codex really struggled with a task I asked Claude to try.

To get the project started I began with an empty folder, opened up the Codex chat window in VSCode, and entered the following

I want to “vibe code” a tool for personal use that I will probably also release on Github. The tool’s purpose is to help someone manage the job search process. I envision it as a web app with a backend and frontend that run locally, but could in theory be hosted. How can I best communicate to you what I want and how to steer the development process?

Codex responded with a requirements template to fill in. I cracked open a cold one and filled in the template (adding about 1000 words) to describe the high-level goal, the pages I wanted to see, a description of the data model, and some aesthetic preferences. I then gave the contents of the file to Codex and it got straight to work with creating the Next.js project and so on. I intentionally didn’t get too detailed when writing the requirements because I was curious how the LLM would fill in the gaps - this was my way of leaning into the vibe.

Model and Pages#

To distill what I had filled into the template Codex gave me, I think it makes sense to just focus on the data model and pages. This will be enough to know what I expected the basic shape of the LLM’s output to be.

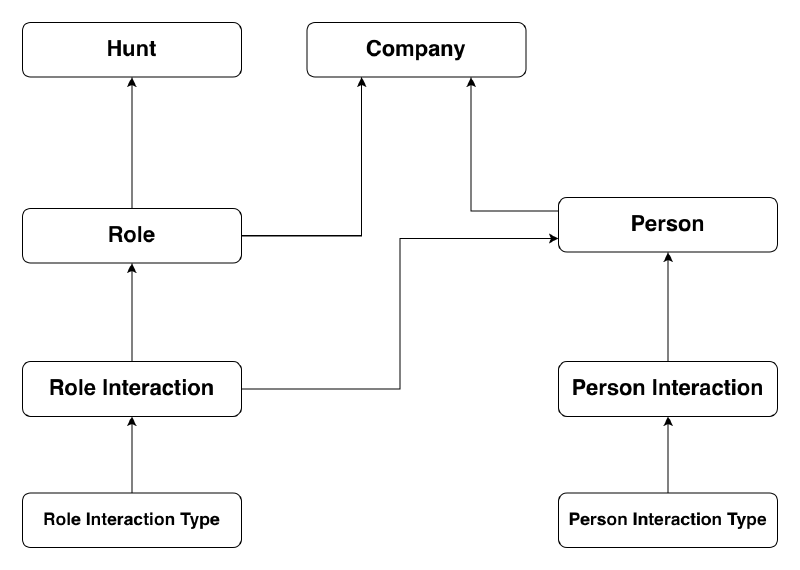

The data model leans on the basic side, but it is sufficient for what Sigh does. The following is a simplified version of the data model that focuses on the core functionality.

- A

huntis a collection ofroles, - A

roleis associated with ahuntand acompany, - A

personis associated with acompany(e.g., a recruiter) - A

roleis associated with manypersons viainteractions. - A

role_interactionis an interaction the user had with a role during the hunt (e.g., application submitted, interviewed, chatted with recruiter). - A

role_interactionhas arole_interaction_type. Users can create newrole_interaction_types to cover their specific cases. - A

person_interactionmimics the same behaviour asrole_interaction, but for people.

The general idea is one will create a hunt, track roles in that hunt, and as they move through the process they can track any interactions they had while pursuing a given role. To do this, Sigh needs only a basic set of pages:

- List of hunts.

- Hunt detail page with list of roles.

- Role detail page with description, associated people, and list of interactions.

- Person list page.

- Person detail page.

- Company list page.

- Company detail page.

The Experience#

The development process was like one long chat. I had the Codex pane open in VSCode, gave directions, responded to requests, and interacted with the app as it was built.

The Positives#

Codex made getting a functioning Next.js application up much faster than I ever could have myself. Within just a few hours I already had a handful of pages up with basic functionality.

Often I would be unsure of how I wanted to lay something out (e.g., nav bar, interactions list, colour palettes) and so I’d ask Codex to give me a few options. It was quick to flip between its proposals so I could easily prototype different ideas with little effort.

Codex built a great input field we called FastInput. The idea was when creating a role, the dropdown to select the company also allowed one to filter by typing. If a company with that name didn’t exist, one could hit enter to open a modal to quickly create a company, and then that company would become the selected option in the dropdown. Codex was able to generalize this pattern and we used it for many inputs on the data entry path, which made data entry pretty speedy!

It also didn’t seem to have any issue reasoning about my (admittedly small and basic) data model. As I asked for changes to the model it would understand the basic consequences and update the relevant code.

Building an application this way was interesting and kind of addictive. By directing the LLM with plain English instead of handcrafting each line myself, I found I had made more mental space to step into the seat of a user, and was steering the development priorities more towards user stories and away from technical concerns.

The Negatives#

I found that Codex was able to get the basic structure up and going quickly, but that it wasn’t very good at polished UI and sometimes was a bit lazy (for lack of a better term). It could be a result of my under-specification, but I found Codex didn’t have a good notion of quick data entry. In the template I filled out for Codex I said:

Sigh will have a special emphasis on data entry being quick to prevent users from delaying data entry and misremembering details.

Despite this, I found that most of the forms were very basic, required a lot of mouse movement, and the modals it created for data input didn’t even focus the cursor. Without a doubt the grand majority of time I spent vibe coding Sigh was on instructing Codex on how to make the UI quick and easy to use.

It was a common occurrence for Codex to place UI elements in strange places or apply the wrong styles, despite having placed the same element several times before on other pages. For example, even though there were plenty of running examples on how to place and style an edit button, it often failed to take the appropriate context into account. This is what I mean by lazy. I found it sometimes didn’t look for what contextually made sense, and just did the easiest thing that could be understood as success.

I knew the anecdotal reports about how quickly someone could turn out a fully functioning application were too good to be true, but part of me really wanted to believe. Sigh isn’t even a highly polished application, and the polish that is there took a ton of back and forth (i.e., time). I’d be floored to learn that others generating user interfaces aren’t hitting the same problems.

Adding Claude#

I hit a problem with styling a markdown editor UI that Codex was just not making a lot of progress on. This was the first problem I handed off to Claude to see if it was any better than Codex. I had instructed Codex to add a WYSIWYG markdown editor on the role detail page for keeping free-form notes about the role. It used mdxeditor to do this, but had just the damndest time trying to style it, in addition to picking a version that had compatibility issues with the version of Next.js I was using. I must have gone back and forth 15+ times with Codex on the UI controls for the markdown editor not being styled correctly, or there being some bug with scrollbars showing when they shouldn’t have. I then explained to Claude that I am having it do a task that Codex was struggling with and hoped for a better result. It took noticeably fewer than 15 iterations for Claude to do it, but the interactions with it were just like the ones with Codex - it confidently proclaimed the problem was fixed, despite no changes that my human eyes could detect.

It’s difficult for me to say if Claude did any better in general. I gave Claude around 10 different tasks that Codex was struggling with, but I was very unscientific in how I did the comparison between the two, as I mostly just let Claude start off from where Codex stopped trying. It may very well be that Claude is better at this type task in general, but there wasn’t some obvious night-and-day difference I could observe.

The Result#

To show the result here’s a quick screen recording. It doesn’t demo everything, but it does show the main flow of creating hunts, roles, interactions, and people.

Conclusion#

I built an app that has been on my to-do list for some time, and I did it much faster than I would have by hand. In fact, the promise of it taking noticeably less time was what actually got me around to building it.

I’ll probably continue to build things this way. Vibe coding makes it much easier for me to prototype ideas, explore unfamiliar stacks, and build small tools for myself that I’d otherwise never prioritize. For that use case, it’s a big win.

That said, the experience did not give me confidence in letting LLMs run large chunks of work autonomously. Any task that wasn’t trivial needed meaningful guidance, iteration, and correction. That isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it does mean I wouldn’t trust the output to be production-ready without going through it with a fine-toothed comb. If real money or reputation were on the line, I’d expect to find plenty that still needs adjusting.

Looking back on it, the process itself is kind of amazing. Through (a rather extended) dialogue, I ended up with a useful tool I was unlikely to ever build otherwise. Maybe the time savings wouldn’t be as dramatic for an experienced Next.js developer - but I’m not one, so the savings matter to me!